October 2021

rust unburnish’d

10 October 2021, around 18.17.

The sort of lazy Sunday on which one has to work because one was having a sort of lazy Friday and a lazy Saturday, but Monday will come with its deadlines, and one does not like to disappoint. Somehow, last week, I managed to write my to-do list on the wrong day in my planner, putting everything one week ahead, and the resulting contrast of a page too blank and a page too full upset the order of things and made it difficult to uncover right action. So, in addition to tracking some dubious changes, I only made time to keep up with The Faerie Queene and Tolstoy’s Cossacks, a comfortable pairing, but unexpected. Crossing things off as I get to them.

Only on Saturday was I able to make progress, at long last, in reading the first volume of a history of the Polish and Lithuanian union, the chapters of which are often as not named for towns in which treaties were signed that tended to cause more problems than they solved, because they were unimaginative, or because their future interpreters were more excessively so. I was hoping for information about how paganism worked then, but the book seems more interested in politics and border raiders and levies of dubious success, as well as the historian’s occupational perk of judging one’s predecessors, medieval and modern alike. So many personalities. A very bowre of blis.

bettered novels (55)

12 October 2021, around 14.44.

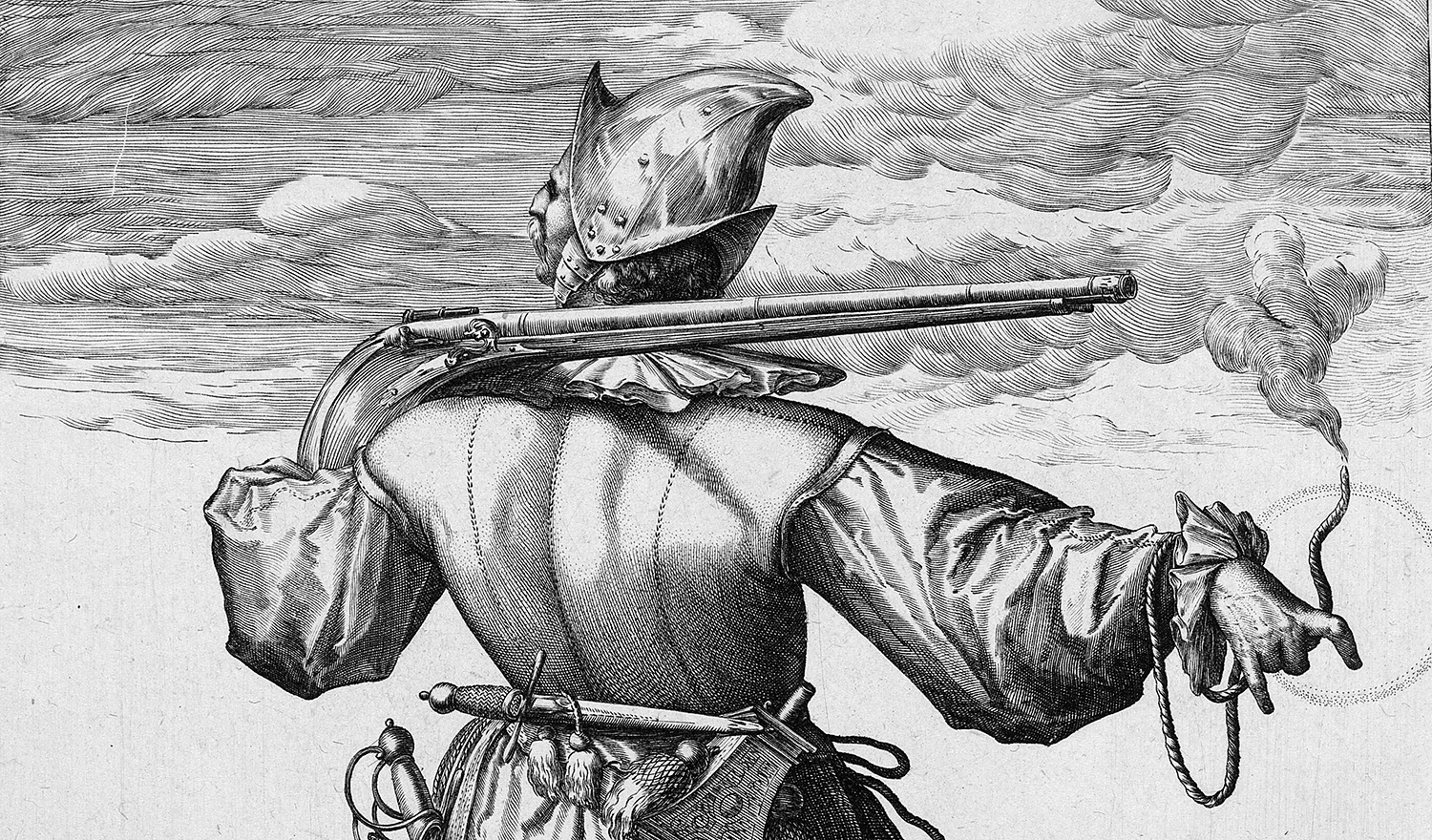

Detail from an engraving of a Helmeted Musketeer (1587) by Jacques de Gheyn II after Hendrik Goltzius

Is The Three Musketeers a great book? It is even a good book? It’s difficult to say. When I started reading it, I approached it as a potentially great book, as part of a foolish, half-hearted project, and found myself almost instantly depressed by it. Although its outlines of character types (there are only three four types of people…) are a notable feature, their lack of broader applicability or substance to ballast the somewhat superficial humor (they have nothing on Theophrastus or La Bruyère) meant that, for me at least, they did not linger.

That could, however, be the result of the constant clattering of the plot’s mechanics, a breathless juggernaut pulled pell-mell by the fell beast serialization. Never a dull moment. But the keen edge of even the most poignant moment becomes dull, if it is forever slashing against one’s attention. I found myself setting the book aside, forgetting about, for months on end. When I saw it, I felt not interest at what would come next or desire to know how the plot(s) would resolve, but resentment. The machinations were convoluted, the motivations improbable, and I was entirely out of sympathy with all of the characters, heroes and villains and everyone in between, from landlords to cardinals, from servants to queens. D’Artagnan’s horse, that sweet little (ugly old) buttercup (bouton d’or), seemed to me the only noteworthy character of the bunch.

* * *

The book improved markedly when I ceased to consider it a ‘great’ book, one that would have the potential to reveal greater depths on rereading. I read the last half of the book rapidly, often half-asleep, and it seemed, if not richer and more varied, at least more diverting. In that sort of rapid, distracted stupor, one scarcely notices that the inaptly named Constance appears to have had a complete personality transplant by the end of the book, going from canny minor insider to idiotic ingénue in need of rescue, or that the Cardinal, bane of the musketeers and perfect machiavel, has gone through multiple roles, including sinister demon, tiresome bureaucrat, disappointed lover, and mediocre manager of loose cannons. Is it a great book? No, ultimately I think not. But it is a perfectly fine book for its purpose – as entertainment, diversion, distraction. As I read, half-amused by the theatrical posturings of Milady, it seemed like the perfect book to read on vacation, when one is sunburnt or has caught an unseasonable cold or it is raining and one cannot go outside and there is nothing else to read, but one has a room or a comfortable chair to oneself and can sprawl as untidily as the plot, perhaps reading aloud choice bits to whoever happens to wander into the room. Yes, it is perhaps a great book for that.

distant views

15 October 2021, around 10.53.

Amazing what one finds in old folders. So many possibilities. (ca. 2002)

with abandon

18 October 2021, around 5.34.

— Is it OK, do you think, to stop reading a book without finishing it?

— What do you mean by ‘finishing a book’?

— Getting to the end of it.

— So you think that if someone takes up a book and turns all of the pages until he (the exemplar is invariably a he, for which I will offer no apology) reaches the end, that one could say he has ‘finished’ the book?

— Well, no.

— Why not?

— Because he hasn’t read it!

— Ah! What do you mean by ‘reading’?

— Well, you know, looking at all of the words on the page.

— So if our friend with the book looked at all of the words on all of the pages, then could we say that he has finished it?

— Depends on whether or not he understood it.

— Interesting. What do you mean by ‘understand’? And what, by the way, is the referent for ‘it’?

— Um, well, I guess by ‘it’ I meant the meaning of the words, and by ‘understand’, um, well, I meant, um, understand.

— Let’s look at that first part: how does one know the meaning of a word?

— Look it up in a dictionary – or ask somebody.

— So if our fine friend looked up all of the words on all of the pages in the book (acknowledging that there would be some duplication) in the dictionary (or asked someone more knowledgeable), could we then say that he has finished the book?

— Well I think he would certainly be done with it! But unless he understood how the words fit together – no, I don’t think we could say that.

— Oh? The words on the page convey a meaning together greater than that which they convey individually?

— Of course they do!

— You say that as though it were the most natural thing in the world, but return to that dictionary you mentioned. If you turned all of the pages of the dictionary and ‘understood’ (and I haven’t forgotten that we still haven’t clarified what we mean by that) all of its words, would you say it has a greater, more comprehensive meaning than the merely lexical?

— No one reads the dictionary cover to cover!

— Why not?

— That’s not what it’s for!

— Oho! So different books have different purposes?

— Of course!

— So when you asked if it was OK to stop reading a book without finishing it, I take it you were not asking about dictionaries. What kind of book were you thinking of?

— Jeez. You know, like – a book: the kind of thing you get when you go into a bookstore looking for something to read. It’s just … what I mean is, I saw an article online about how you have to read more than just the first few chapters of a book to really be able to judge it and—

— Wait. All this time we were talking about reading and what it means to read and how one can say that one has read a book and what a book even is, and you were really interested not in reading, but in judging?

— Well … yes, I suppose so, yes.

— And who are you to judge?

— I … like to read books?

— But didn’t you just say judging is distinct from reading?

— Um, no, actually, you said that, but I guess I didn’t, don’t disagree, but that’s not… you know what? Never mind.

pseudaphoristica (22)

24 October 2021, around 6.22.

To describe a place requires more than the negative space of one’s impressions.

25.x.2021

25 October 2021, around 6.08.

‘Good carpentry can make a secret door in any wall.’ —William James, from Essays in Psychical Research

up the road

25 October 2021, around 9.22.

point d’appui

27 October 2021, around 6.16.

At Saint Sulpice.

(Obvious limits to such an undertaking: even when my goal is just to observe, I don’t see what takes place a few meters from me: I don’t notice, for example, that cars are parking)

Aisha Sabatini Sloan’s Borealis: An Essay (2021) was commissioned as the first in a series of essays inspired by Georges Perec’s An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris (1974/5). Perec’s Attempt is a curious work, describing three days at the Place Saint Sulpice without wading through architectural or historical narrative (as I recall, no particular emphasis is placed on the police station, the district council building, the punning fountain, no ghosts of the Commune save the pigeons, although none of these are avoided, either); it consists mostly of lists capturing movement or a panorama (signs, the repetition of passing busses, groups of Japanese tourists, the recollected contents of grocery bags) and snapshots of individual moments (a wedding, a funeral, and I recall the lighting of a cigarette, but that could be misremembered). This information is presented as though from field notes, which are dated and sometimes timestamped; it is tied to the physical, the mundane, the quotidian – in fancy dress as a neutral account of what could be seen by any attentive observer on those particular days (not especially noteworthy) at that particular place.

Unlike Perec, Sabatini Sloan chooses not to describe a narrow segment of her own hometown, Los Angeles, but rather attempts to exhaust the town of Homer, Alaska (‘the end of the road’, as Tom Bodett calls it in his NPR-flavored writing about the town), which she had visited several (three?) times over the years for various reasons, in various degrees of (dis)comfort. The town is not clearly delineated, but remains amorphous, shifting – here a glacier, there a museum, a seal skull fetched by a dog, eagles through hearsay or the screen of a phone, weapons concealed and unconcealed, blank eyes – seldom seen. There are many names, personal reminiscences – situations, situatings: the text drawing attention to its references, trying to sit in a web of meaning, as though being caught in a web creates its own meaning. Perhaps it does.

One of us kept disappearing, appearing suddenly in a crowd.

Although working in a quasi-anthropological mode, the manner and content of Perec’s observation of Place Saint Sulpice are inseparable from his character as observer, which itself must be situated: clever, inventive, his parents Polish Jews who did not survive the war (a feeble euphemism). As Perec’s text elides his presence, heightens the sense of absence, as though the lists, the timelines, were the product of an invisible eye or a CCTV camera, big data, not a person with hopes and dreams, a past and a future – he appears with a sense of weariness, wariness, only to emphasize what he cannot see: The apparent lack of judgment is itself a judgment, and the ‘neutralization’ of the observer’s position is pointed. (I’m not certain this is an entirely accurate assessment, as it has been some time since I read it and I do not have a copy to hand.)

Sabatini Sloan does not work within the anthropological tradition, but rather provides a writerly notebook, wastebooks (grey A4, marbled B5), pointedly personal and all too present and visible as observer: ‘the other mixed girl’. The attempt to exhaust the end of the road does not exhaust the place so much as the reader – in part because of the blatant contempt felt for the people encountered (the inhabitants cannot tell the narrator apart from ‘the other mixed girl’ – just as the narrator can scarcely tell [or wish to tell] the diner hostess apart from Sarah Palin) and in part because it does not engage with the place (with white supremacy, with racism) directly but does so via mediation – through Björk, Anne Carson, Renee Gladman, Robin Coste Lewis, (the too-White) Iron and Wine, Lorna Simpson, This American Life, Donna Tartt, etc., etc. – not encountered ‘organically’ in Homer but borne in with the baggage, underlining (increasing) the distance between observed and observer: I’m not from here and I don’t want to be (this could, however, be another pointed absence). The book does not so much exhaust Homer, Alaska, as evade it entirely – it is not a place, but a shorthand for estrangement: Outopia.

This irritates without satisfying – but irritation is a natural consequence of a broken system, so let us say that this, too, was intentional.1

- In Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, Sharpe discusses a class she teaches on memory, in which she pairs the teaching of the Holocaust with the legacy of trans*Atlantic slavery; her students find it easy to see the Holocaust as the main point of compassion, the star of history’s pageant of monstrosity, but find it difficult (if even possible) to give the same kind of attention to the narratives of the Middle Passage or Jim Crow (or Ferguson). She initially taught the events chronologically, but that led students to think of the account of slavery as an opening act, so she started to teach the Holocaust first – without, it seems, achieving the desired effect. It is a difficult effect to achieve, and I think this in part encapsulates my difficulty in appreciating (or feeling sympathy with) Borealis – it hits too close to home. [↩]