January 2014

Citation (50)

1 January 2014, around 14.58.

For I have taken to getting up again. I thought I had made my last journey, the one I must now try once more to elucidate, that it may be a lesson to me, the one from which it were better I had never returned. But the feeling gains on me that I must undertake another. So I have taken to getting up again and making a few steps in the room, holding on to the bars of the bed. What ruined me at bottom was athletics. With all that jumping and running when I was young, and even long after in the case of certain events, I wore out the machine before its time. My fortieth year had come and gone and I still throwing the javelin.

A Publisher Speaking

3 January 2014, around 5.20.

A Publisher Speaking is a collection of five talks about the book industry given to various audiences between 1931 and 1934 by Geoffrey Faber, the founder of Faber and Faber. The contents of the volume are as follows:

- On Bookselling (i): A Publisher Looks at Booksellers (1931)

- On Bookselling (ii): The Relations between Bookselling and Publishing (1931)

- On Publishing (i): Book Trade Problems and Policy (1933)

- On Publishing (ii): Are Publishers Any Use? (1934)

- On Censorship: Notes on a Proposed Literary Censorship (n.d.)

Many of the suggestions Faber makes have been followed in the book industry. Independent booksellers especially make more of an effort to ‘promote lectures, entertainments, exhibitions, readings, and the like’ (33) – the manner of selling books hasn’t really changed since 1933, though the market has.

More interesting than his ideas about bookselling, though, are his ideas for the regulation of the publishing industry. In an idea that may come from Stanley Unwin’s The Truth About Publishing,1 Faber supports the idea of licensing for publishing firms – that is, requiring potential publishers to pay a yearly fee to set up shop and publish books: so much for so many novels each year (136–141). As he says rather more brutally:

What is wrong with publishing is that there are too many publishers, and far too many books (135).

Licensing would, Faber thinks, resolve both of those problems. Moreover, there was already an organization in existence that could manage the process: the Publisher’s Association, of which Faber was for a time the head (106f.) It was not undertaken, due in part to the war-time restrictions on publishing and the later evolution of corporate media conglomerates, which ensured that publishing stayed in the control of the wealthy few – though not those who cared about the quality of literature.

Books & articles to add to reading list

- Stanley Unwin. The Truth About Publishing. London: Allen & Unwin, 1946 (1926).

- Which I will have a look through later. [↩]

in stacks

3 January 2014, around 5.21.

A few books close at hand.

Her favourite reading was a mouldy old book called Urn Burial, that she read in bed; and she liked creepy, rustling things like tortoises and cacti. She had a dark, haggard face that made one think of an old graveyard, but her eyes were so dark and deep that when one talked to her, one talked into her eyes, the way one drops a pebble into a pool to watch for the ripples.

In reading an old anthology of short stories (Modern English Short Stories: Second Series), I happened to like one by Frances Towers – who does more than describe sitting rooms – and her posthumous collection Tea with Mr. Rochester did not disappoint.

Crambe repetita (31)

4 January 2014, around 5.02.

Runner beans, with fresh green foliage and small but bright red flowers in summer, clambered over dilapidated little arbours drenched with lingering, grey autumnal mists and the dull, stale cold of winter without frost and snow.

The door Franz opened was rusty. All the allotments seemed to be an ocean of rotting cabbage stalks. Here and there, white snowdrops came creeping quietly out from under the rubbish. You didn’t see them creeping, just their whiteness.

Franz saw Schleimann. He was sitting on a rickety little seat in his arbour, right hand on the handle of a spade, left hand on the handle of a small hoe. The allotment felt like a graveyard where no one rested in peace, and it smelled of murder.

A view (40)

8 January 2014, around 16.37.

It rained most of the day.

pleasant & agreeable

9 January 2014, around 12.00.

It’s dreary out.

He is a learned man, and has a power of college-books by heart: his greatest fault is, that he incessantly quotes passages from them in conversation, which is not agreeable to everybody.

Years ago my mother used to say to me, she’d say, ‘In this world, Elwood, you must be,’ – she always called me Elwood – ‘In this world, you must be oh so smart, or oh so pleasant.’ Well, for years I was smart. I recommend pleasant. You may quote me.

- Translated by Tobias Smollett. [↩]

undetectable

12 January 2014, around 15.11.

A down-graded storm.

There are of course other things I should be doing, even other things I should be reading, but just at the moment detective stories seem to be what I want. They are amusing and plotty and charmingly shamefaced. There’s not a one that takes itself too seriously, not one that claims it will last longer than empires, not one that poses or postures as anything but what it is: a detective story. Of course they do not mind nodding and winking at the reader, with protestations of ‘lawd, I wouldn’t believe it if I read it in a book’ or ‘you’ve read too many detective stories’ at some improbable turn of the plot – though one detective even goes so far as to credit a mystery he’d read with helping him to solve the case.1 Neither here nor there; suffice it to say that I’ve been reading detective stories and am not quite sure what will come of it.

- The Rasp, p. 230. [↩]

from that other place

17 January 2014, around 20.58.

If one grows up in Oregon, one hears a lot about William Stafford. Always being the sort of person to avoid what other people are talking about (with no regard for its merit or interest), I never read any of his work until just a few months ago – and I expected to sneer even then.1 This is not a very good start, especially when I was planning to read a new (to me) collection of poetry every month and write about it – this is a very bad start indeed.

Anyway. I happened to read ‘A Way of Writing’. My expectations were low – but the humility and sensibleness of the essay left me (slightly) chastened and I set my sneering aside (for the moment). I even went to far as to attend the launch for Winterward, published by the local press last December, Of course since I attended the launch, an eminently respectable affair in a downtown chapel, I thought I might as well pick up a copy; once I had a copy of the book, I figured I might as well read it, so here we are. If you’re not familiar with Winterward, it’s William Stafford’s doctoral dissertation from the University of Iowa and this edition is the first time that these poems have been published as a collection with Stafford’s introduction.2 This is all fine and good, but what I like about the book, what I liked about the launch event, was the atmosphere of the thing: the way that the presenters burnt incense (as it were) on the altar for the poet, for his character, and for poetry in general – and the way that this resonated with the uneasy deism of the collection.3 It is quite a religious set of poems, concerned with God and souls and how one balances against authority, as in the following poem, ‘Fieldpath’:

I helped make this groove,

and other helpless monuments I have

carved—turning them over this evening,

I see no way to escape immortality:

my shadow with its Christian name

has worn out through this grass so long.

One could say that this poem, too, is a track in the grass – an eminently perishable, transitory path that might yet be more durable than grass and cram more than eternity into an hour. The body is the shadow-self, and the real self – not bumbling along, yet still curiously powerless to contend with shadows – is what? the soul? the mind? Whichever it is, it is at odds with its labels, its Christian name. I don’t want to wrestle more with this poem; perhaps because it could win, but in any case because I would certainly lose, have certainly lost – I must acknowledge that it was interesting to read the collection, and it was interesting to be surprised by it. Perhaps, slowly, I shall learn to achieve a greater share of receptivity, as Stafford counsels:4

Maybe I have to settle for an immediate impression: it’s cold, or hot, or dark, or bright, or in between! Or well, the possibilities are endless. If I put down something, that thing will help the next thing come, and I’m off. If I let the process go on, things will occur to me that were not at all in my mind when I started. These things, odd or trivial as they may be, are somehow connected. And if I let them string out, surprising things will happen.

- I am fond of sneering; it is not a nice thing about me. I don’t mean anything by it, really, except liking to sneer, but people do seem to take it the wrong way and it would be better if I stopped. Where was I? Right. Preparing to sneer at William Stafford – a provincial poet; a regional poet – and if there’s anything I like worse than a poet, it’s a regional poet. [↩]

- Most of the poems in the collection have been published elsewhere, and will be quite familiar to readers of Stafford’s work. [↩]

- This was not at all what I expected: nature poems – yes; god poems – no. [↩]

- It has taken a great effort not to deflate this attempt to write about poetry with sneering at this point – especially by puncturing the notion that I am interested in the exercise at all. Well, I suppose I have managed to be very nearly sincere. Or I hope so, anyhow. The final quote is from ‘A Way of Writing’ in case you hadn’t guessed that. [↩]

detected

20 January 2014, around 15.10.

(8) Finger-prints of any value to the police are seldom found on anybody’s skin.

(9) The pupils of many drug-addicts’ eyes are apparently normal.

(10) It is impossible to see anything by the flash of an ordinary gun, though it is easy to imagine you have seen things.

(11) Not nearly so much can be seen by moonlight as you imagine. This is especially true of colors.

(17) Even detectives who drop their final g’s should not be made to say anythin’ – an oddity that calls for vocal acrobatics.

(18) Youse is the plural of you.

(19) A trained detective shadowing a subject does not ordinarily leap from doorway to doorway and does not hide behind trees and poles. He knows no harm is done if the subject sees him now and then.

immeasurably

30 January 2014, around 7.00.

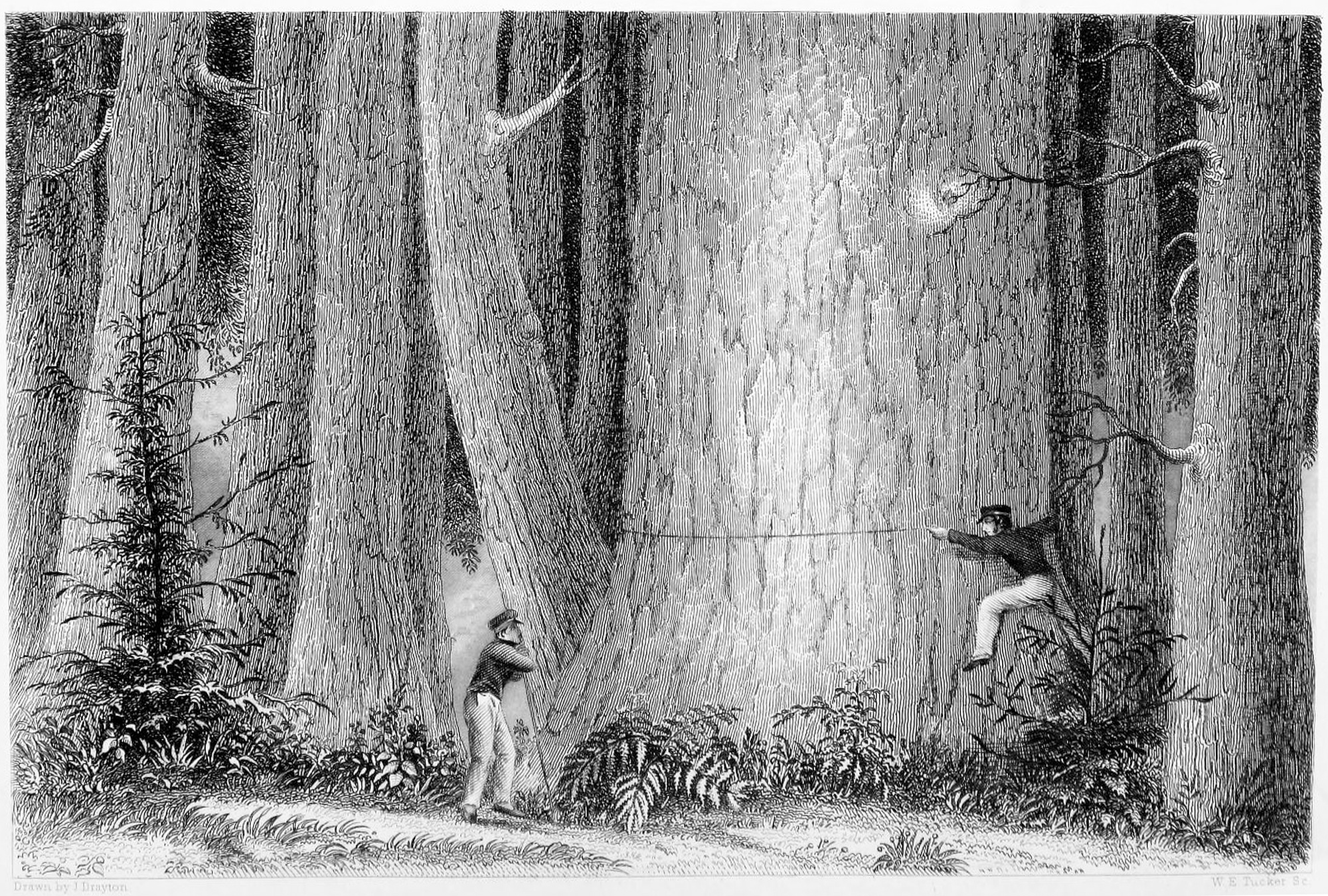

J. Drayton, ‘Pine Forest, Ore.’1

- Just something I found one day – a pebble as it were, to generate ripples of thought. Later (March 2022): After checking the original of Wilkes’s Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition (vol. 5), it appears the original sketch was by Drayton; the caption has been updated accordingly. [↩]