November 2003

inscriptiones graecae

1 November 2003, around 9.02.

Tangier has been mentioned in history for three thousand years. And it was a town, though a queer one, when Hercules, clad in his lion skin, landed here, four thousand years ago. In these streets he met Anitus, the king of the country, and brained him with his club, which was the fashion among gentlemen in those days. The people of Tangier (called Tingis then) lived in the rudest possible huts and dressed in skins and carried clubs, and were as savage as the wild beasts they were constantly obliged to war with. But they were a gentlemanly race and did no work. They lived on the natural products of the land. Their king’s country residence was at the famous Garden of Hesperides, seventy miles down the coast from here. The garden, with its golden apples (oranges), is gone now — no vestige of it remains. Antiquarians concede that such a personage as Hercules did exist in ancient times and agree that he was an enterprising and energetic man, but decline to believe him a good, bona-fide god, because that would be unconstitutional.

Down here at Cape Spartel is the celebrated cave of Hercules, where that hero took refuge when he was vanquished and driven out of the Tangier country. It is full of inscriptions in the dead languages, which fact makes me think Hercules could not have traveled much, else he would not have kept a journal.

Crambe repetita (2)

3 November 2003, around 18.00.

… καὶ σὲ πολλὸν ἀνθρώπων

ἐγὼ φιλέω μάλιστα, ναὶ μὰ τὴν κράμβην.

…and of all mankind, I love you most especially — yes! by the cabbage!

notify me

7 November 2003, around 10.02.

Powell’s promises to tell me when these books come back in stock:

- Indexing Books by Ruth Canedy Cross

- Travels in Arabia Deserta, 2 volumes, by C. M. Doughty

- Garland of Philip, 2 Volumes, by A. S. F. Gow

- Book of Trances by Güneli Gün

- On the Road to Baghdad by Güneli Gün

- Alpha and Omega by Jane Ellen Harrison

- Roman Foundations of Modern Law by H. F. Jolowicz

- Indexing, the art of: a Guide to the Indexing of Books and Periodicals by G. Norman Knight

- Cicero’s Letters To Atticus: 7 Volume Set by D. R. Shackleton Bailey1

- Yes, I am kicking myself for not picking up the 7-volume ad Atticum when they had the set (not even ex-library!) for $400. It is such a shame that, though libraries are nice, possessing a personal library is so much nicer… [↩]

A view (11)

10 November 2003, around 16.05.

3.52 p.m.

I feel sick

11 November 2003, around 8.50.

It began with the pulp of a pumpkin which was kept in a cookpot atop the dishwasher on Halloween. Why it was kept, I know not. After a week, however, even I knew it stank. Indeed, to the very heavens. The future eminent medievalist concurred, declaring she felt nauseated. Once the windows were opened and the pot was washed, I mentioned, as practising pedant, that I found the word nauseated distasteful—why use a four-syllable word when the perfectly good nauseous is a mere two? The future eminent medievalist rounded on me; if you have never been rounded on by a future eminent medievalist, I cannot say I recommend it. She told me in no uncertain terms that I was simply wrong (an idiot—an imbecile—a pedant of impecunious wit!), that to be nauseous was the characteristic of those things which nauseate others, while to be nauseated (which I had always understood as the past tense or participle of the verb to nauseate, rather than as an independent adjective1 ) was the only correct term for feeling sick to the stomach (unless of course one wishes to say one feels sick to one’s stomach). I said I found the discussion noxious, and there the matter ended. Or would have.

Whether the future eminent medievalist had recourse to a dictionary, I cannot say; as I have been in the habit of saying that I feel a bit nauseous when inclined to be sick, I thought I’d better get my facts straight before I say anything of the sort again. To the OED. Under nauseous (Google results: 103,000):

1. † a. Of a person, the stomach, etc.: inclined to sickness or nausea; squeamish. Obs. rare.

1613 R. CAWDREY Table Alphabet. (ed. 3), Nauseous, loathing or disposed to vomit. 1651 J. FRENCH Art Distillation V. 144 It may be given..to children or those that are of a nauseous stomack. 1678 J. RAY Coll. Eng. Prov. (ed. 2) Pref., I have..so veiled them, that I hope they will not turn the stomach of the most nauseous.

b. orig. U.S. Of a person: affected with nausea; having an unsettled stomach; (fig.) disgusted, affected with distaste or loathing.

1949 Sat. Rev. 7 May 41 After taking dramamine, not only did the woman’s hives clear up, but she discovered that her usual trolley ride back home no longer made her nauseous. 1955 R. LINDNER Fifty-minute Hour i. 41 Always when he thought of his mother Charles would feel a little sick; not actually sick perhaps nauseous was the better word. 1977 Washington Post 15 May C4/1, I would go into the bathroom late at night and put hot and cold compresses over my eyes. I’d feel queasy and nauseous. 1991 Times 2 Aug. 12/4 When a toadlicker licks the toad his mouth and lips will become numb and he will feel intensely nauseous. 2000 Shop@home No. 7 21/4 If the thought of Xmas makes you nauseous, maybe you need to get away.

2. lit. a. Of a thing: causing nausea. In later use: esp. offensive or unpleasant to taste or smell.

1628 J. WOODALL Viaticum 13 To giue a relish to the mouth, to cause appetite in feauors and nautious distempers. 1647 N. WARD Simple Cobler Aggawam 27, I have no heart to the voyage, least their nauseous shapes and the Sea, should work too sorely upon my stomach. 1744 G. BERKELEY Siris §1 This method produceth tar-water of a nauseous kind. 1781 W. COWPER Hope 509 The full-gorged savage, at his nauseous feast Spent half the darkness. 1807 T. JEFFERSON Let. 14 June in Writings (1984) 1178 Such an editor too, would have to set his face against…slander, & the depravity of taste which this nauseous aliment induces. 1841 DICKENS Barnaby Rudge vii. 273 Cured by remedies in themselves very nauseous and unpalatable. 1875 A. HELPS Social Pressure vi. 80, I used to eat the nauseous bits first. 1904 J. LONDON Sea-wolf ii. 13 It was a nauseous mess, ship’s coffee,but the heat of it was revivifying. 1933 P. FLEMING Brazilian Adventure II. ii. 191 We landed on a beach strewn with jatobá nuts, of which we subsequently made a dish as nauseous as any I have ever tasted. 1987 M. WESLEY Not that Sort of Girl (1988) xxxii. 173 Mylo took the nauseous brew handed to him in a tiny medicinal glass.

Compare nauseated (Google results 59,900):

Originally: † causing nausea, cloying, rank (obs.). Now: suffering from or characterized by nausea.

1659 Gentleman’s Calling (1696) 163 Forsaking all the unsatisfying nauseated pleasures of Luxury. 1673 R. ALLESTREE Ladies Calling I. i. §3 To entertain new scholars only with the cast or nauseated learning of the old. 1759 SIR C. H. WILLIAMS Wks. (1822) II. 262 The nauseated reader, no longer cou’d brook The hoarse cuckow note. 1876 G. MEREDITH Beauchamp’s Career II. i. 7 Offering our nauseated Dame Britannia (or else it was the widow Bevisham) a globe of a pill to swallow, that was crossed with the consolatory and reassuring name of Shrapnel. 1891 G. MEREDITH One of our Conquerors III. vii. 131 His renewed enslavement set him perusing his tyrant keenly, as nauseated captives do; and he saw, that forgiveness was beside the case. 1962 K. A. PORTER Ship of Fools 85 He..took a dose of effervescent laxative salts, making the same nauseated face after the draught. 1990 Daily Tel. 4 Dec. 19/1, I got out of bed, but felt dreadfully giddy, nauseated and then panic stricken.

Going by the great dictionary2 it seems that nauseous has been on a boomerang semantic shift since the seventeenth century, with its active usage (‘causing nausea’) peaking in the queasy Victorian age.3 Going by Google, nauseous is clearly the more popular word and, notes on this question excepted, generally seems to mean ‘feeling sick’. Fans of usage will be murmuring (as they always do) that the nauseous/nauseated quandry is not new; indeed, it has been covered from almost every perspective, from the merely prescriptive, the dryly non-commital (American Heritage Book of English Usage, 1996), to the rather more instructive. I will not investigate further; I am satisfied; the future eminent medievalist and I were both correct, and we were both wrong, too. The score is settled. I really do not care which word you use—the context will tell me whether you are suffering from nausea or self-loathing. I must say, though, that the sort of person who begins ‘proofs’ of usage with the phrase ‘I was taught that…’ make me sick. One can be taught many facts without learning to think.

- But I am not a linguist—doubtless the ultimate meaning is the same, no matter what one calls it. [↩]

- The OED is in this case sadly out of date—couldn’t they find a more recent use of ‘nauseous’ than Shop@home? Or were the editors trying to make a point about vulgar usage? [↩]

- I really am wondering about the absolute silence on the passive use of nauseous (suffering from nausea) between 1678 and 1949, and would also like to know why it returned. [↩]

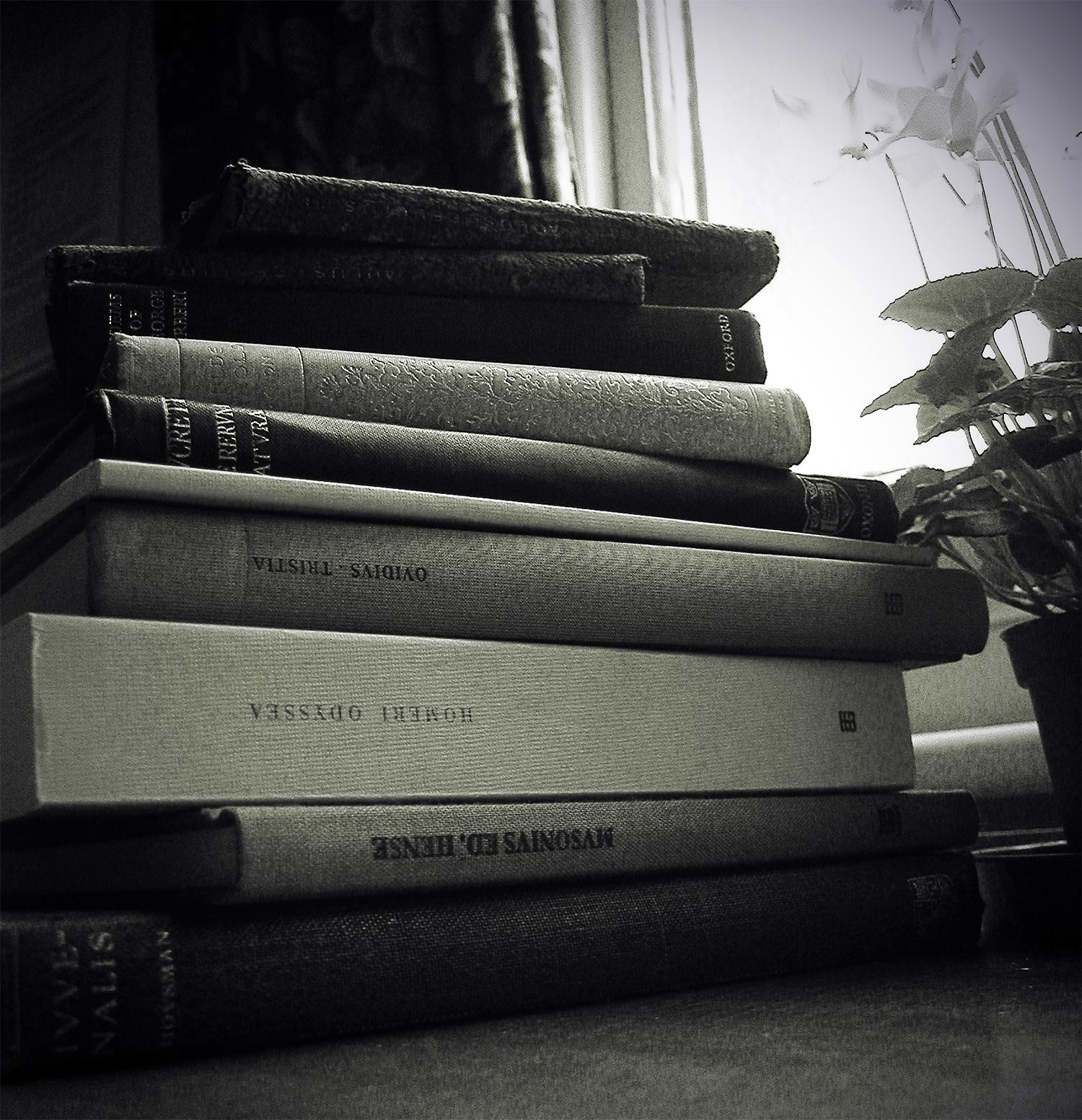

ex-libris

13 November 2003, around 8.40.

To be saved in the event of fire, flood, incipient exile: Juvenal’s Satires (Cambridge, 1931), Reliquiae of Musonius (Leipzig, 1990), the Odyssey (Leipzig, 1993), Ovid’s Tristia (Leipzig, 1995), Epistulae Tres et Ratae Sententiae (Epicurus; Leipzig, 1996), De Rerum Natura (Oxford, 1922), Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, complete poems of George Herbert, & Noctes Atticae (Aulus Gellius; Leipzig, 1878).

Sadly, I cannot say if I am actually the sort of person who would ‘save’ these particular books, or if that is merely the sort of person I would like to be; hopefully time won’t tell.

dedication

14 November 2003, around 12.38.

Although the new A. S. Byatt collection Little Black Book of Stories is something of a disappointment because three1 of the five stories have been published before, the last paragraph in the book book almost makes up for it:

Finally, this book is dedicated to my German translator and to my Italian translators, all good friends and precise readers. Talking to them over the years has changed my writing, and my reading (279).

Quite. In all, though, wait for it to come out in paperback, then borrow it from a friend; unless, of course, you like Byatt’s work a very great deal indeed — in which case enjoy, as the collection is thoroughly typical.

- ‘The Thing in the Forest’ (New Yorker, 3.vi.2002); ‘Body Art’ is in The Phantom Museum and it described as leading ‘the collection of stories and essays from the front, like some big, bold, burgundy sedan trailing a convoy of smaller and less colourful cars behind’; and ‘Raw Material’ (The Atlantic Monthly, iv.2002). [↩]

fructus

15 November 2003, around 13.22.

…eritis sicut diis scientes bonum et malum…

malum punicum vel punica fides?

Citation (13)

17 November 2003, around 17.28.

Notions and scruples were like spilt needles, making one afraid of treading, or sitting down, or even eating.

irreptitious

20 November 2003, around 10.08.

Into my heart an air that kills

From yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.

The weeping Pleiads wester,

And the moon is under seas;

From bourn to bourn of midnight

Far sighs the rainy breeze:

It sighs from a lost country

To a land I have not known;

The weeping Pleiads wester,

And I lie down alone.

* * *

The rainy Pleiads wester,

Orion plunges prone,

The stroke of midnight ceases,

And I lie down alone.

The rainy Pleiads wester

And seek beyond the sea

The head that I shall dream of,

And ’twill not dream of me.

Some can gaze and not be sick,

But I could never learn the trick.

There’s this to say for blood and breath,

They give a man a taste for death.

More of Housman’s poems are available elsewhere; see also the fragment of a Greek tragedy & the (sadly abridged) ‘Application of Thought to Textual Criticism’. Rather unrelated: index to the Housman Society Journal, with the titles – but not the texts – of articles few people have time to read anyway.

grave & weatherworn

23 November 2003, around 6.08.

Scaliger was far from untouched by the religious troubles of his day, but the way they bedevilled the scholarship of the sixteenth century is more starkly illustrated in the case of his friend and younger contemporary Casaubon. Born in Geneva of refugee Protestant parents, obliged to learn his Greek hiding in a cave in the French mountains, unable to avoid being drawn into the wrangle because of his distinction as a scholar and forced to spend much of his time and talents on arid polemic, this great French scholar finally found rest as a naturalised Englishman in Westminster Abbey. With him the French scholarship of the period ended, as it had begun, on a chalcenteric1 note. He was a man of vast industry and erudition, but had the rarer gift of being able to use his learning as a commentator to illumine rather than impress. He appears to have chosen to work on those texts that offered the most scope to his wide knowledge, such as Diogenes Laertius, Strabo, and Athenaeus. His choice of difficult and often diffuse texts, with which most students of of the classics have but a passing acquaintance, means that his services are not always recognized. For Casaubon is still with us. His Animadversiones on Athenaeus formed the core of Schweighäuser’s commentary of 1801, Strabo is still usually cited by reference to Casaubon’s pages, his notes on Persius loom large in Conington’s commentary. Son-in-law to Henri Estienne and for a time sub-librarian to de Thou at the royal scripts, Casaubon was most at home in the world of books and manuscripts, able to find material for his own needs and to supply scholars all over Europe. His use of manuscript material has not been properly appraised, but he seems to have made no dramatic advances, except that his second edition of Theophrastus’ Characters (1599) added five more characters (24–8) to those then known. Some of his most distinguished work was long buried in his unfinished commentary on Aeschylus.

- A word which should be used more often in casual conversation; literally, bowels of bronze — hence tough, vigorous or sturdy. [↩]

- According to Powell’s, this belongs in the reference – trivia section. Personally, I think it belongs in the classical literature section, but that’s just me… [↩]

prosopopœia (1)

23 November 2003, around 18.04.

… or, an introduction to the history of classical scholarship1

The imminent schollrs of the 6/10 century — including the fatuous Scaliwag who eateded Easelbus, and the imperspicuous Käseböh who collected Athenians and fatted xviii chiliads — are now seldom dead but by kabbalists.

- The text is believed to be corrupt, the manuscript tradition poor, and the editor on a tea-break. [↩]

A view (12)

30 November 2003, around 18.36.

florid capitals