it would do beautifully

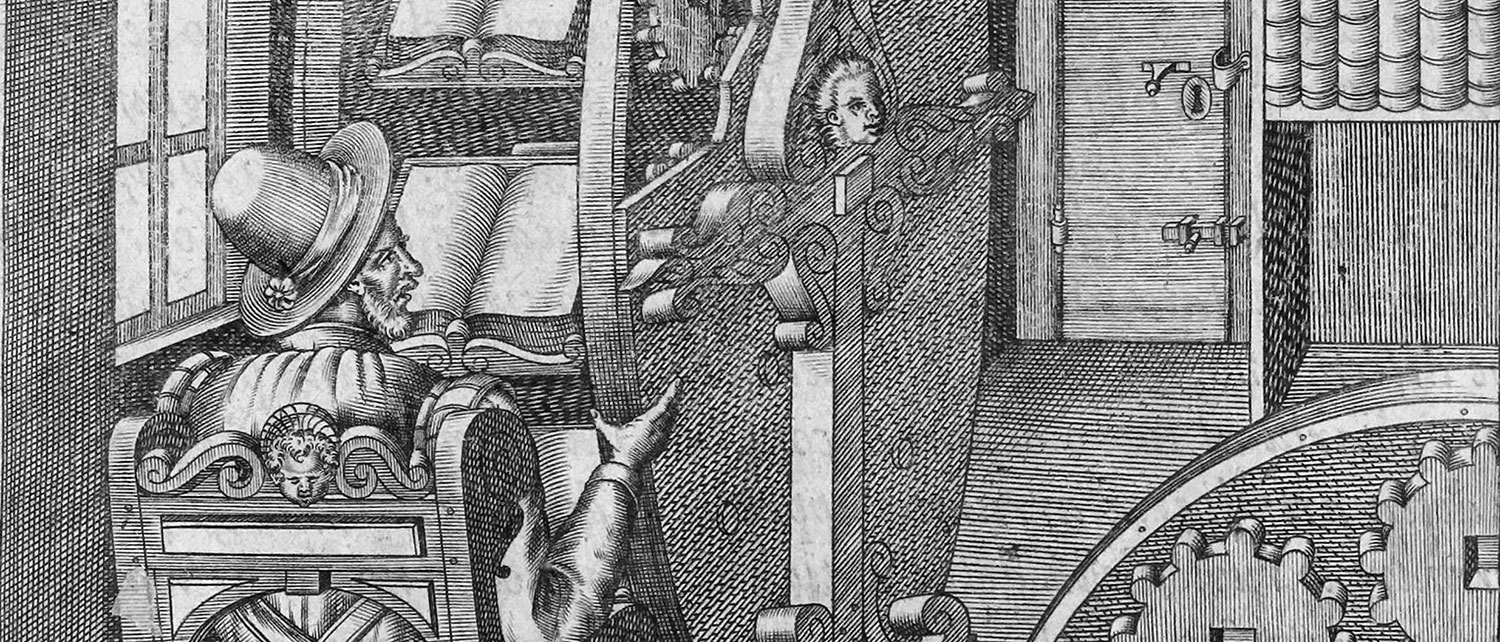

The inconstant reader.

… I reminded him how often we had talked about my travels on the five continents and sixteen seas, and my inability to stay very long in one place. Although I was living peacefully in Pollensa, there was not guarantee it would be permanent.

The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll is a melancholy book. It’s not a sad book, or a depressing one, but it drifts in a sombre current. More important, to me, it captures the inward and outward sense of movement travel creates in a more familiar way than any other book I’ve read – recently or not. I think, though, that I was primed to like this book; I read it at the right time, and in a way (with a sort of eager lethargy, if that makes sense) that prevents me from forming any sort of critical or objective judgement about it.1 I kept meaning to write about it, but found that I couldn’t, and still can’t, really.

All the stories and lies about his past accumulating until they formed another being, always present and naturally more deeply loved than his own pale, useless existence of nausea and dreams.

The strangest thing to me was the way in which Maqroll reminded me of Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, which I didn’t much like at all: both tell of two unhappy men who travel (together and separately) to diverse ends; both use the trope of the ‘false document’; both are violent and oversexed. Yet I liked Maqroll and disliked The Savage Detectives; perhaps because the protagonists in The Savage Detectives were running away from themselves, while in Maqroll they are restless and mobile because that is simply what they are – it is their nature.

If it did not sound so pedantic, one might speak of Hellenic charm. A serenity suddenly shaken by tremors of foreboding, as the signs of an overwhelming revelation that never comes, as if time, without really stopping, had changed the rhythm of its passage and granted us a moment of eternity.

- If indeed forming any sort of critical or objective judgement about anything is possible at all, which I’m beginning to think it isn’t. And why should the thoughts and assertions about a book one didn’t particularly like or wasn’t in the mood for at the time be more valid than the less explicable reactions one has to a book that hits you at the right time in the best possible way? The explicability has to be the point, but it’s an overrated one. [↩]