April 2003

of Vices and Virtues

1 April 2003, around 18.03.

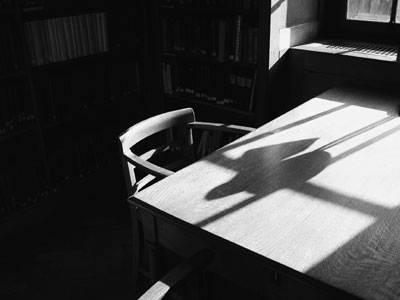

Library, sunlight, nine a.m.

Our breach of hospitality went to my conscience a little: but I quickly silenced that monitor by two or three specious reasons, which served to satisfy and reconcile me to myself. The pain which conscience gives the man who has already done wrong, is soon got over. Conscience is a coward, and those faults it has not strength enough to prevent, it seldom has justice enough to accuse.

the Third Day

3 April 2003, around 20.49.

It was the third day, I think—it has been so long, you see, I have almost forgotten. This forgetfulness comes from habit, I suppose—days numbered to the umpteenth power ratcheting one to the next, the turning of the mechanism grown monotonous, something simply there but scarcely noticed. Not like at first, when each day seemed miraculous, when each day was truly new, like a painting that abruptly catches your attention (no matter how often you think you saw it), grabs your glance so suddenly that you stand in front of it for hours or minutes, scouring it with your eyes, lifting away each brush stroke, the minutest variation in color, the texture of the canvas and the splintered gilt on the frame, stealing it away to keep in your most private collection. As I said, it was a long time ago, and you must forgive me if I’ve forgotten the exact order; my memory for these things is not what it was. A grudge I can remember, but the order of those early days… not so well as I used to.

So it was the third day and everything was still; no cattle crushed the grasses of the hillside, no dogs trotted along the sidewalks tugging or dawdling at the lead, no birds perched in the branches, no fishes disturbed the sea, not an insect moved. I am trying to remember that sound. It is not what we now think of as silence, that sterile stillness which yet contains the buzzing of florescent lamps, or the muffled rasp of our own frightened breathing, or the slow settling of walls and floors and rafters. No, it was not silence at all. Nor was it truly noise, because if it were noise, then it could cease, and that cessation of sound would be silence. I think it was at that moment, that instant just after I had noticed land on the horizon, land covered in grass and trees and more things than even I could have imagined, it was just then, I think, that I noticed the air had a sound of its own. The gales dashing over the waters when water was all there was, for those years, or months, or days, or hours had yet been unproductive of sound, because there was nothing but the wind and the waves; there was no distinction, no differentiation, hence no need to notice. But when I saw the land… I’m not sure how to explain it. I was suddenly aware of the breezes rustling the grasses, tossing the branches of the trees to and fro, dashing the leaves against each other. It was not startling; there was no din, no clatter, nothing to frighten or astound, because the sound had always been there—I simply hadn’t noticed it.

It’s an odd thing to think about, that sound. But I’ve been reminiscing—it’s not as though there’s been much call for me in recent years or I could be of any real use. Anyway. Even though it seems funny now, looking back on it, I recall wondering at the time if the land was some mistake, an error conjured out of the waters, a primeval garden of folly. Of course, it didn’t have a hermit then, it being only the third day. It was certainly accidental; I certainly did not mean to start anything. It might have been an error. Even now, I can admit that it all might have been a mistake. Now, of course, no one will believe me. They have other things on their minds—those grudges I mentioned, for one; but let’s not begin all that again. No, let’s not start that at all—we only end up going in circles, arguing causation and shifting the blame, going round and round like the soundless hurricanes on the surface of those waters so many, many years ago.

a Record of Consumption

10 April 2003, around 21.18.

Including: Sterne; Novalis; Keats; too many Brontës; Chopin; R.L. Stevenson; Chekhov; Modigliani; Kafka; etc.

Among other things: Vico, The New Science; A.A. Cooper (Earl of Shaftesbury), Characteristics of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times; Pepys Diary: 1665 (ed. Lantham et al., vol. 6); Dos Passos, U.S.A.; dental floss; shampoo; oat cakes; muesli; rice crackers.

Also: tea (whole leaf Assam, steeped 3½ minutes, soy milk, 3 cups); coffee (fair trade, dark roast, cafetière, steeped 4 minutes, soy milk, 2 cups); muesli (with raisins and soy milk, 1 bowl); vegetable lentil soup (with crumbled double gloucester, 1 bowl); water (from the tap, in a glass, lost count).

accidental augury

11 April 2003, around 11.06.

Two birds, perfectly white, pink-beaked, dark-eyed, pigeons, settled on the ledge outside my window, billing and cooing as birds will in spring. Startled, I stood hunched, half-risen from my seat at the desk, the pages of a book leafing shut; over the point where their shoulders would be my movement caught their eyes, and they were gone.

Along the peak of the friary wood pigeons bow and sway, a nimble gavotte upon the dark red tiles.

Sunday

13 April 2003, around 15.36.

Not a lot of sun hazing through the clouds or the drifting petals from the pear tree in the back. The madwoman on the bench talks at the people waiting for the bus, Go’ blessh you, my chil’, Go’ blessh you; one man turns, delivering in pure Oxbridge and God bless you, as he steps onto the bus. Seven flies buzz from the open window; I’m in need of a tailor or poet to deal with them.

Consumers of Culture

14 April 2003, around 14.43.

It is only through difference that progress has been made. What threatens us right now is probably what we may call overcommunication—that is, the tendency to know exactly in one point of the world what is going on in all other parts of the world. In order for a culture to be really itself and to produce something, the culture and its members must be convinced of their originality and even, to some extent, of their superiority over the others; it is only under conditions of undercommunication that it can produce anything. We are now threatened with the prospect of our being only consumers, able to consume anything from any point in the world and from every culture, but of losing all originality.

If culture, then, is something of a construct, should it come as any surprise that its consumers wish to follow the latest fashion? All my life I wore a raincoat, until I saw an umbrella—I cannot say the one is better than the other (for everything there’s a pro and a con), yet I’ve given up my customary coat (admittedly an eyesore with its blueberry color and red trimmings) to endanger the eyes of others with the spokes of a brolly. Should I therefore lament? When there are no raincoats left in the world, or but one or two, or if the purveyors of parasols prevent persons preferring alternative protection from the elements from pursuing that choice—why then yes, I shall be sore vexed, wax wroth, etc., etc. But excuse me, I am spluttering, nor is the comparison of culture and raingear particularly apt, though perfectly arbitrary; more suitable, perhaps, is this query:

…have not the wisest of men in all ages, not excepting Solomon himself,—have they not had their Hobby-Horses;—their running horses,—their coins and their cockle-shells, their drums and their trumpets, their fiddles, their pallets,—their maggots and their butterflies?—and so long as a man rides his Hobby-Horse peaceably and quietly along the King’s highway, and neither compels you or me to get up behind him,—pray, Sir, what have either you or I to do with it?

But culture is not a hobby-horse—or is it? One talks so much about it, compares it with so many other things, becomes defensive, sensitive, irate, one forgets in the end what it is. And what is it? I’m sure I don’t know.

the end of English letters

15 April 2003, around 8.10.

April 9 [1937]: VirginiaWoolf’s The Years and F. Tennyson Jesse’s A Pine to See the Peep Show read at once—what with rain and fairies and walloping bells at Oxford and Missie dying of love for Teacher with a dash of beans and fish with the lower middle class—impress one again with the constipation of English letters. They copy this sentence 100 times—‘England is Jolly, Tea is Good, Rain is Nice, Oxford’s Heaven, Teacher is Peachy, I’ll be Buggered.’ Then they make their individual curleycues, Miss Woolf with air and sea and esprit at her command, others with mere patience and paper. The same things happen to the same families only it’s Ron instead of Don and Winnie instead of Binnie. I do not know whether on this small island only a few patterns are possible in life for a writer to record, or whether people, well-read on their own fiction, dare not allow their lives to step out of fiction’s prescribed patterns. It’s a conventional country, after all.

- Cf. ‘…she is wittier than Dorothy Parker, dissects the rich better than F. Scott Fitzgerald, is more plaintive than Willa Cather in her evocation of the heartland and has a more supple control of satirical voice than Evelyn Waugh, the writer to whom she’s most often compared’: review of a biography of Dawn Powell (NY Times). [↩]

now that’s quality

16 April 2003, around 8.18.

Having finished reading Randall Jarrell’s1 first novel, Pictures from an Institution (1954),2 I now understand why people go ga-ga for Kerouac: general American fiction of the 1950s was rotten.3 Take offense if you will, but I stand by my statement. When seen against the backdrop of such insipid, feeble prose as Jarrell’s, where flashes of wit last no longer than a firefly’s flickering (and provide, if I may say so, rather less illumination), Kerouac’s writing, for all that it is petulant, adolescent, and puerile, (I need some more synonyms here, people), at least has some spark. On the Road is an unpleasant, sniveling, arrogant, narcissistic, toadying gangbang of a novel, devoid of grammar, of wit, and rampant with snobbiness, but at least it has even that much character: one can speak of it as a personality. Pictures from an Institution lacks even that; it has all the dynamism of wet cardboard.

Don’t get me wrong—it’s a lovely book: I could imagine people liking it, admiring the deft pencil sketch qualities of some of the portraits; fireflies of wit can be admired, if admiring fireflies is your sort of thing. But heavens to Betsy, the thing isn’t permanent! (Would that I had left it in the stacks, mouldering, gathering dust as it deserved!) And if you’re not going to write a novel for all time, then what the devil are you writing a novel for anyway?4

- Yes, I know he is better known as a poet; that’s no excuse. [↩]

- Would that the title did not remind me of Mussorgsky’s ‘Pictures at an Exhibition’: I was suffering from the Great Gate of Kiev the whole time I was reading. [↩]

- Not, actually, that I read much of it. In fact, I rather wonder if this little rant is not going to join the legion of embarrassing literary judgments I’ve made (the most notorious of which came in declaring, at age twelve, that Pride & Prejudice had no plot—yes, I learnt the error of my ways, thank you very much). Somehow I doubt it. Winter 2010: actually, yes. [↩]

- General note: this entry brought to you in part by Claude Lévi-Strauss, who observed (in 1977 on a Canadian radio program) that pop music was killing the novel—or actively burying it if, in fact, ‘the novel’ were already dead. [↩]

Loot

17 April 2003, around 16.18.

Such dim-conceived glories of the brain

Bring round the heart an undescribable feud;

So do these wonders a most dizzy pain,

That mingles Grecian grandeur with the rude

Wasting of old Time—with a billowy main—

A sun—a shadow of a magnitude.

Allow me to sound heartless for a moment. (Or even more heartless than usual, however you want to think of it.) As everyone knows, unknown persons have plundered the Iraqi National Museum of Antiquities in Baghdad, and the armed forces of the ‘Coalition’ have been unable to stop them, despite knowledge of the dangers to and the importance of these artifacts.1 Anyone concerned about the history of civilization is het up about this looting, and rightly so; it is an abomination, they observe, and they rhapsodize on the missing items, harps and tablets and museum records burnt for heaven-only-knows what reason.

But I want to know something: why the outrage? Looting of this sort is nothing new. Go to your local museum, especially if it’s one of those really nice ones, like the Metropolitan or the Louvre or the British Museum. You know what you see?

Loot. Plunder. Spolia.

The people who painted those funerary masks or carved those statues or mummified those cats sure as all hell didn’t intend them to be shuffled into barbarian warehouses for the ‘education’ or ‘improvement’ of gibbering hordes. Every time you marvel at the geometric vases at the Met, or the Elgin marbles,2 or the Hammurabi stele, you are benefiting from the plunderers of the past. Don’t you forget it.3

And the destruction of artifacts? Nothing novel, nothing strange: bombed in wars or thieved through time, beauty’s immortality is brief, despite our hopes. We get upset about it, we worry about the loss or destruction of the masks of long dead kings, shattered Buddhas, temple relics, because it forces us to confront our own mortality, our histories?’ finitude: no matter what monument we build, no matter what artistic legacy we hope to leave behind, memory’s finite.4 Wanton destruction of the past—individual, communal, civic, national, international—is one of the things we’re best at; the history of human existence is the history of the rubbish heap, and sometimes we throw important things away.

It’s a shame—but it’s always been our shame, if only we had cared to acknowledge it.

- It is an odd image, though—a museum needing a tank to defend it. Shouldn’t a society’s respect for its heritage be all the guard it needs if, in fact, the museum is doing its job? [↩]

- The Elgin marbles being, of course, that portion of the Parthenon marbles filched in the early nineteenth century by a now notorious Scotsman. [↩]

- But at least they’re on public display, you cry, anyone can see them; that’s obviously better than they’re being squirreled away for the private enjoyment of the privileged, where they might be damaged by poor conditions and mishandled by the ignorant. (Curious how museum entry fees are rising, especially the suggested ‘donations’… and did you know you oughtn’t to use chisels to clean marble?) But at least scholars know where the artifacts are, which is more than can be said for looted material. (Ha! Doesn’t mean they use it, though.) Though it is, of course, all far more complicated than that… [↩]

- And how much do we really value those cuneiform tablets if we don’t spare the time, energy or funds to publish them? [↩]

Poor, obscure, plain & little

18 April 2003, around 9.27.

Spring, 8:39 a.m.

May 16 [1962]: Thinking of modern education (such as Lake Erie) which is to instruct a person how to be unable to survive alone—exact opposite of original purpose. How to get along with the community; how to mask your differences and to whittle off your superior gifts to level down with the lowest; how to follow, not to lead; how to be helpless without material goods; how to run machinery; how to be a slave to your home and family; how to do without thinking and let your individual talent atrophy or die aborning. Reading, Latin, Greek, walking, etc.—these give the greatest joys to a person without money, alone, sick. The present education presupposes the person will never be old, sick, alone, poor or unpopular.

fortitude

19 April 2003, around 12.35.

Men who have an eye for trouble, men who know that tiny causes have given birth to very great disasters, are full of worry at every unusual event, and, when their troubles are at the zenith, they fear for the outcome and tremble at every harassing rumour. Even if their luck turns, they still cannot believe it. On the other hand, there are the simple-minded folk, who neither suspect the origin of future troubles nor bestir themselves to deal with the cause of their woes. They have an inclination for pleasures and they desire to revel in them for ever. What is more, they like to convert strangers to the same way of thinking. In order to live a peaceful existence, to follow their peaceful pursuits, they tell the rest of the world, with the air of soothsayers, that they will find swift relief from their grievous misfortunes. There is also a third class of people, with a finer temperament. If trouble should come upon them surreptitiously, it does not catch them unprepared. Certainly their ears are not dimmed with the crashes and noise around and outside them. Trouble does not scare them, cannot cow them into surrender. On the contrary, when all others have given up in despair, these persons stand imperturbable in the face of peril, relying for support not on material things, but on the soundness of reason and on their own superior judgement. I must admit, though, that so far I have not met with men of that sort in my lifetime.

febrility

20 April 2003, around 8.57.

about 3 o’clock.

The Diseases and Casualties this Week

23 April 2003, around 8.19.

London 39 · From the 12 of September to the 19 · 1665

| Abortive | 23 |

| Aged | 57 |

| Bedridden | 1 |

| Bleeding | 1 |

| Cancer | 1 |

| Childbed | 39 |

| Chrisomes | 20 |

| Collick | 1 |

| Consumption | 129 |

| Convulsion | 71 |

| Dropsie | 31 |

| Drowned 3. one at Stepney, one at St. Katharine near the Tower, and one at St. Margaret Westminster | (3) |

| Feaver | 332 |

| Flox and Small-pox | 8 |

| Found dead in the street at St. Olave Southwark | 1 |

| French pox | 1 |

| Frighted | 1 |

| Gangrene | 1 |

| Grief | 1 |

| Griping in the Guts | 45 |

| Head-mould-shot | 2 |

| Jaundies | 3 |

| Imposthume | 6 |

| Infants | 10 |

| Kingsevil | 1 |

| Lethargy | 1 |

| Meagrome | 1 |

| Plague | 6544 |

| Plannet | 1 |

| Quinsie | 3 |

| Rickets | 20 |

| Rising of the Lights | 15 |

| Rupture | 4 |

| Scowring | 3 |

| Scurvy | 2 |

| Spotted Feaver | 97 |

| Stone | 1 |

| Stopping of the stomach | 5 |

| Strangury | 2 |

| Surfeit | 45 |

| Teeth | 128 |

| Thrush | 6 |

| Timpany | 1 |

| Tiffick | 4 |

| Ulcer | 1 |

| Vomiting | 2 |

| Worms | 15 |

| In all | 7690 |

| Males · | 3783 |

| Females · | 3907 |

| Plague · | 6544 |

The Aßize of Bread set forth by Order of the Lord Maior and Court of Aldermen:

A penny Wheaten Loaf to Contain Nine Ounces and a half, and three half-penny

White Loaves the like weight.

The list is, as Henry James might put it, suggestive. One wonders about the person frightened to death, or the one who died of grief. There is something faintly humorous, too, in the poor soul ‘Found dead in the street at St. Olave Southwark,’ as though being ‘in the street at St. Olave Southwark’ were somehow the essential cause of death. Not, of course, that the Bills of Mortality were primarily concerned with the cause of death as such, being a mere table of corpses, but the need to assert some authority over death—even by listing the manner, if not the cause—is as touching as it is futile. Also:

- John Graunt’s Natural and Political Observations mentioned in a following index and made upon the Bills of Mortality: ‘Autumn, or the Fall is the most unhealthfull season’ (cf. Hippocrates, Aphorisms).

- Macabre London: extracts from the Bills of Mortality.1

- Old disease names and their modern definition (with discussions generated by the topic).

- Cf. Mortality statistics in England and Wales.

- Cf. also the classification of mortality from the CDC: terrorism codes.

- This was an exhibit at the Museum of London which sadly they have taken offline. [↩]

Poetastery (2)

24 April 2003, around 20.17.

…or, a Triolet occasioned by the coming of Spring.

Perverse and pertinacious Pigeon,

depart, I pray you, from the gutter—

or else thy bastard beak I’ll bludgeon,

perverse and pertinacious Pigeon!

I’ve lingered long in too high dudgeon,

and murd’rous imprecations mutter…

Perverse and pertinacious Pigeon,

depart, I pray you, from the gutter!

Part the Fifth

25 April 2003, around 12.48.

Zealously denying the accusations, Richard waxed eloquent in his own defense. Words of unimaginable beauty, wit and intelligence poured forth from his rosy lips as he flaunted the erudition acquired by years of wearing navy blue jackets at elegant institutions at the expense of some unnamed patron. The company at the table listened attentively, their faces glowing with ardent admiration at his oratorical prowess. His eyes flashed with righteous indignation, but his voice betrayed not a hint of anger as he expounded quite logically all the reasons why he could not have pocketed a butter knife—neglecting to mention, of course, that his inner pocket was unfortunately sewn shut as he had only just discovered before he dropped the knife onto the floor.

Citation (7)

27 April 2003, around 11.06.

The art of literature consists exactly in this passage from the Eye to the Voice. From the wealth of nature to that thin shadow of words, that gramophone. The Readers are the people who see things and want them expressed. The author is the Voice, or the conjuror who does tricks with that curious rope of letters, which is quite different from real passion and sight.

The prose writer drags meaning along with the rope. The poet makes it stand on end and hit you.

One wonders, though, how the ‘thin shadow of words’ became a ‘gramophone’ in the duration of one word, two spaces, and a comma. Although he set up the image, a bit, in the preceding sentence, he does nothing to support it, so it does not add much to the sense of his argument. Hulme being an Imagist, I suppose the meaning should lag, as thunder does, behind the lightning-flash of images; yet allow me to be momentarily catholic in my taste—I thought it simply sloppy.

Which just goes to show how easy it is to miss the point of the excerpt, which is, of course, the wonderful image of the ropes.

Terrible learning, Mr. Newman

29 April 2003, around 7.34.

Correctly,—ah, but what is correctness in this case? This correctness of his is the very rock on which Mr. Newman has split. He is so correct that at last he finds peculiarity everywhere. The true knowledge of Homer becomes at last, in his eyes, a knowledge of Homer’s ‘peculiarities, pleasant and unpleasant.’ Learned men know these ‘peculiarities,’ and Homer is to be translated because the unlearned are impatient to know them too. ‘That,’ he exclaims, ‘is just why people want to read an English Homer,—to know all his oddities, just as learned men do.’ Here I am obliged to shake my head, and to declare that, in spite of all my respect for Mr. Newman, I cannot go these lengths with him. He talks of my ‘monomaniac fancy that there is nothing quaint or antique in Homer.’ Terrible learning,—I cannot help in my turn exclaiming,—terrible learning, which discovers so much!