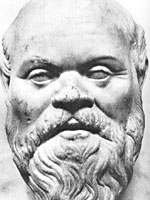

Socrates Silenos

Began reading The Mask of Socrates: the Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity, and was struck by the following passage:

The earliest portrait of the philosopher originated about ten to twenty years after his death and shows him in the guise of Silenus. In flouting the High Classical standard of beauty so blatantly, this face must have disturbed Socrates’ contemporaries no less than his penetrating questions (32).

Please note the similarities:

|  |

| Socrates (Roman copy of Greek original, ca. 380BC) | Silenus (Italian antefix, ca. 470–460BC)1 |

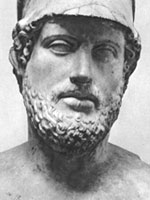

Pericles

(ca. 440BC)

Why would a pug-nosed Socrates be ‘disturbing’? Taken on his own terms, I suppose he wouldn’t be, but of course the portrait, like the individual it represented, could not be taken on its own terms—so take a moment and compare the portrait of Socrates with the slightly earlier portrait of the statesman Pericles. Note the regularity of Pericles’ features, the trimness of the beard, the overshadowing helmet signifying the concern he bore to protect Athens; note, too, the impassive gaze, the lack of wrinkles. The portrait is idealized on so many different levels it would be difficult to enumerate them. Return to Socrates. The nose, which next to that of the Silenos had seemed almost moderate, now verges on the grotesque; the laugh wrinkles at the eyes (which may, admittedly, be a Roman addition) complement the full, jovial cheeks somewhat lacking in Periclean seriousness; the bald head and rather unkempt beard suggest a man unconcerned with keeping up appearances—which in an age of appearances (when virtue is a matter of kalokagathia) is almost unpatriotic.

Walter Benjamin

Whether a perfect profile is a civic virtue and a pug nose the mark of barbarism is for those more learned in aesthetics to decide. Whether the artist who sculpted the portrait of Socrates meant to make a ‘statement’ supporting Socratic measures of goodness (as Zanker hints) is open to dispute. That one’s idea of an ‘intellectual’—and what one expects from such a person—can and has been shaped by images is not to be doubted. ‘viewers find in this face what they look for, based on their personal preconceptions of the subject, especially … where the different renderings of the expression in the various preserved copies seem at different times to favor one or another interpretation’ (40). Zanker describes the photograph at right as ‘Walter Benjamin looking out at the viewer, his head propped on his hand, his face filled with loneliness and weltschmerz’ (333).2 Is this what people today expect of the ‘intellectual’, loneliness and weltschmerz—is this mere ivory-tower romanticism? Other images may be useful (e.g. Derrida, Said).3

- The original link

http://www.clevelandart.org/exhibcef/mg/html/8906609.htmlhas rotted, but the piece is in the Museo Archeologico Regionale di Gela, inv. 8294, cat. no. 63. There’s an article about the Cleveland exhibition in Minerva Magazine [PDF!] from 2002. Cf. a rather more human antefix in the Walters Collection. [↩] - I would like to know how this iconography differs significantly from the Hellenistic ‘rigors of thinking’ on which Zanker spends an entire chapter (pp.90–145), but not just yet. (I grant you the glasses, but still, the crazy hair, the funny clothes, the hand to brow… there’s got to be more to a modern intellectual than myopia). [↩]

- Zanker’s other well-known book, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (again translated by Alan Shapiro and based on a series of lectures Zanker gave) is also amusing and deals with the overt manipulation of images for political purposes. How far one can agree with Zanker is a matter of opinion, but his books (and articles) are quite enjoyable to read. [↩]