June 2015

Montaigne 1.21

5 June 2015, around 9.16.

We sweat, we tremble, we turn pale and blush through the shock of our imagination and lying back in our feather-bed we feel our body agitated by its power…

- The power of imagination – excesses of sympathy a cause of suffering.

- The case of Marie / Germain.

- Impotence and imagination: ‘his mind and ears had been so beset with fancies, that he found himself fettered by a disturbed imagination…’ (and then had the opposite problem and couldn’t keep it in his pants).

delirium

8 June 2015, around 9.40.

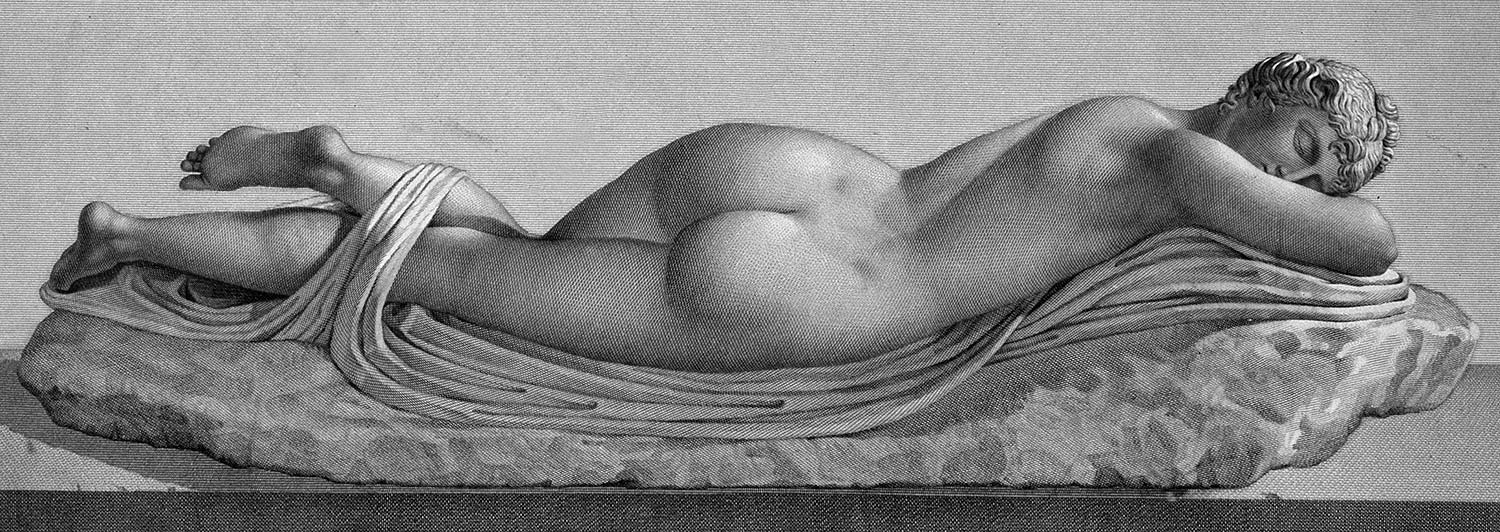

Reading Fiona Templeton’s Delirium of Interpretation, I didn’t quite know what to make of it – I do not believe I have recently read a work that so forcefully put me, as a reader, at such a great cultural distance from the work, its origins, and its meaning. I had a great deal of difficulty imagining what the play would look like on the stage, as so much seemed dependent on the character of actors and the whims of the dramaturge.1 The stage directions are gnomic — ‘this will all make sense in 4 dimensions, in reference to the sculpture’ (87) — and the marginal references to source material distract rather than illuminate, eliminating rather than supporting textual authority. In short, it was not at all what I expected – it irritates and provokes: as it should.

- Indeed, I’ve rarely read a play so much in need of dramaturgical interference. [↩]

Montaigne 1.22

12 June 2015, around 11.00.

The tradesman thrives only by the extravagance of youth, the husbandman by the dearness of grain, the architect by the ruin of houses, the officers of justice by lawsuits and men’s quarrels; even the honour and practice of ministers of religion depend on our death and our vices. No physician delights in the good health even of his friends, says the ancient Greek comic dramatist, nor does a soldier in the peace of his city; and so with the rest. And, what is worse, if each of us sounds his conscience, he will find that his inmost wishes are for hte most part born an nourished at the expense of others.

- I’ll admit I was afraid this essay would become a sort of Roman Way of Death, but thankfully its brevity saved it from that. [↩]

Crambe repetita (37)

15 June 2015, around 5.52.

Much had been happening to him since our holidays together in Cornwall. While I was away in America, he had become engaged to a Guildford girl. Not long afterwards he obtained a good post in Guernsey, was married out of hand, and took his bridge with him to his new home. I had ecstatic letters from him about their small house and strip of garden. It was quite a new experience for Dim to cut and roll the bit of grass, dig the beds, and plant cabbages and peas and beans. He said that every time he came in from College he had to go and see if anything was showing above ground. I had a special letter when the cabbages were visible from the mirror.

My first visit to them ‘to see how they and the beans were going on’ had caused me much excitement in the summer of ’95. It sounded homely and primitive, this island life among the beans and cabbages.

Montaigne 1.23

19 June 2015, around 9.15.

What can be more barbarous than to see a nation where, by lawful custom, the office of a judge is sold, and judgements are paid for in good ready money, and where justice is by law denied to him who has not the wherewithal to pay for it (113).

An odd essay, which starts off with a fairly pluralist Herodotean catalogue of foreign customs – ranging from eating spiders to circumcising women – and then, after a ramble into the power of women to shape the customs of a country, extols faith in right authority, particularly divine law. One feels Montaigne did not follow the line of his thinking – or rather that he did, and was terrified, backing himself into the corner of authoritarianism as a habitual safe haven.1

- Though one where it is possible – indeed recommended – to obey the letter, but not the spirit, of the law. [↩]

Montaigne 1.24

26 June 2015, around 13.22.

Now, I say that not only in medicine, but in several more certain arts, there is a good deal of luck. Why should we not attribute the poetic flights which ravish and transport their author out of himself to his good luck, since he himself confesses that they exceed his power and ability, and acknowledges them to proceed from something else than himself, and to be no more within his power than those extraordinary emotions and agitations of orators, which, as they say, impel them beyond their intention?

It is the same with painting, for it sometimes happens that touches escape from the brush of the artist that so far exceed his conception and his art as to excite his own admiration and astonishment. But Fortune still more evidently shows the share that she has in all these works, buy the charm and beauty which enter into them, not only in spite of the intention, but without even the knowledge of the workman. A competent reader will often discover in the writings of others perfections other than their author intended or perceived, and lend them a fairer face and a richer meaning (123f.)