April 2004

WBY

1 April 2004, around 8.33.

I cannot think of a writer I dislike more than William Butler Yeats; mind you, I’m sure such an author exists – the literary world would be a sad place indeed if the most unlikeable creature it could offer was WBY – but I can’t think of one right now. Aside from being a pompous ass, Edith Wharton said he was ‘fluffy and loveable’ – which is not only no recommendation, but is, in fact, the kiss of death.1 My apologies, of course, to his fans. I have nothing to say against (or for or about) his poetry – indeed, may it achieve such immortality as it deserves. However… oh, forget it.

- The Wharton is from A Backwards Glance – or at least I think it is; it may, in fact, not be from Wharton at all, but from someone I was reading at the same time. I just remember it referred to Yeats and was more apt than anything I could make up myself. If my imprecision makes you weep, I will try to find a more accurate citation, but it could take a very long time indeed. [↩]

Directions to Servants

1 April 2004, around 19.01.

A bracingly absurdist guide to the (mis)behavior appropriate to servants. In addition to a general exhortation to all the household staff to cheat their master and mistress in every way possible, Swift also addresses individual notes to the Butler, the Cook, the Footman (including advice on how to act when going to be hanged), the Coachman (who should be drunk), the Groom, the Steward, the Porter, the Chambermaid, the Waiting-maid, the Housemaid, the Dairymaid, the Children’s Maid, the Nurse (‘If you happen to let the child fall, and lame it, be sure never to confess it; and if it dies, all is safe…’ [70]), the Laundress, the Housekeeper, and the Governess. All are told to look out for their own best advantage and their master’s ‘credit’ – especially if given money in advance to make purchases. Chutzpah is the greatest virtue, and Swift explores its myriad applications with very near his usual vigor. See, for instance, his advice to a footman:

If you are ordered to make coffee for the ladies after dinner, and the pot happens to boil over while you are running up for a spoon to stir it, or are thinking of something else, or struffling with the chambermaid for a kiss, wipe the sides of the pot clean with a dish-clout, carry up your coffee boldly, and when your lady finds it too weak, and examines you whether it hath not run over, deny the fact absolutely, swear that you put in more coffee than ordinary, that you never stirred an inch from it, that you strove to make it better than usual because your mistress had ladies with her, that the servants in the kitchen will justify what you say. Upon this, you will find that the other ladies will pronounce your coffee to be very good, and your mistress will confess that her mouth is out of taste, and she will for future suspect herself, and be more cautious in finding fault.1 This I would have you do from a principle of conscience, for coffee is very unwholesome, and, out of affection to your lady, you ought to give it to her as weak as possible; and upon this argument, when you have a mind to treat any of the maids with a dish of fresh coffee, you may, and ought to subtract a third part of the powder on account of your lady’s health, and getting her maids’ goodwill (38f.)

It is a delightful trifle (as opposed to an agreeable fluff), and I wish Swift had had the energy to develop it further; I suppose the author’s death is as good an excuse as any for not finishing it, but I’m still disappointed.

- ‘If you are a young, sightly fellow, whenever you whisper to your mistress at the table, run your nose full in her cheek, or if your breath be good, breathe full in her face; this I know to have had very good consequences in some families’ (6). [↩]

Crambe repetita (7)

5 April 2004, around 8.18.

What, bred at home! Have I taken all this pains for a creature that is to lead the inglorious life of a cabbage, to suck the nutritious juices from the spot where he was first planted? No, to perambulate this terraqueous globe is too small a range; were it permitted, he should at least make the tour of the whole system of the sun. Let other mortals pore upon maps, and swallow the legends of lying travellers…

Inquiries

7 April 2004, around 13.25.

Lately I’ve been thinking (very slowly) about the word choir and, in particular, its appearance in two familiar poems. The first is Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth‘, and the relevant passage (ll.5–8) runs as follows:

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs, —

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

I like the reversal of expectations; one assumes that the choir will be composed of boys singing dirges, but instead – with the emphasis of repetition – the choir is composed of the shells hissing over no-man’s land. Owen relegates the expected boys to silence in the next stanza (ll. 10–11). Equally silent, but in a different context, are the choirs in Shakespeare’s seventy-third sonnet (ll. 1–4):

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In this metaphorical application to the empty branches of a tree in winter, choir is used in the (quite common) sense of the place in a church where the choristers stand. Again, as in the Owen poem, one senses the failure (or emptiness) of organized religious expression to capture the emotions the author wishes to communicate. But that is not what I want to talk about. Rather, I’m interested in homonymy – in particular, the word quire. In addition to being an alternate (and archaizing) spelling ‘choir’, a quire is:

1. A set of four sheets of parchment or paper doubled so as to form eight leaves, a common unit in mediæval manuscripts; hence, any collection or gathering of leaves, one within the other, in a manuscript or printed book.

2. A small pamphlet or book, consisting of a single quire; a short poem, treatise, etc., which is or might be contained in a quire. Obs.1

In a bound book, the text-block is composed of quires.2 In the case the ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ it adds to the tone of the shells a second quire, a second voice of mourning: the poet’s own; but I do not think this formal parallel was conscious for Owen. For Shakespeare, though, it’s almost impossible to deny the pun. The yellow leaves lingering on the branches might just as well be the leaves of a book – pages which must be unwritten, of course, when the poet dies (just as the branches ‘where late the sweet birds sang’ become ‘bare ruin’d choirs’).3 The full quires containing the sonnets, however, will continue their serenade (dare I say, ‘twittering’?) despite the changing seasons, despite death, in a typical declaration of immortality. I could go on. But I won’t. It is enough that in the printed editions of these poems the words within the quires sing tunefully, recited through the passing years in many voices, despite the silent or demented choirs mentioned.

- This usage is attested after 1450. [↩]

- Now generally called signatures; the perplexed should consult a bookbinder’s glossary or have recourse to a bibliography. [↩]

- Someone must have thought of this already; I, however, have contented myself with reading the sonnets rather than reading about them. If you’ve seen this notion elsewhere, I’d be happy to hear of it. [↩]

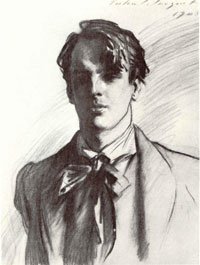

Portrait of the Author

9 April 2004, around 12.14.

Love and Freindship (sic)

9 April 2004, around 18.59.

Of juvenilia I am not a fan, but, in a desire to improve my mind by reading what I do not like, I picked up yet another volume of opuscula published by Hesperus. It should not be surprising that Jane Austen possessed, at the age of fourteen, all the sharpness of observation which would later make her famous. She punctures the conventions of eighteenth century ‘chick-lit’ (see, e.g., the works of Charlotte Smith, Ann Radcliffe, or Mary Hays). She mocks the romantic sensibility and its affectations both physical (‘it was too pathetic for the feelings of Sophia and myself – We fainted alternately on a sofa…’) and emotional:

She staid but half an hour and neither, in the Course of her Visit, confided to me any of her secret thoughts, nor requested me to confide in her any of Mine. You will easily imagine, therefore, my Dear Marianne, that I could not feel any ardent affection or very sincere Attachment for Lady Dorothea.

This would be of little interest, were it not for the transparency with which Austen punctures the narrator’s pretensions and reveals her self-absorption:

Nay, faultless as my Conduct had certainly been during the whole course of my late Misfortunes and Adventures, she pretended to find fault with my Behaviour in many of the situations in which I had been placed. As I was sensible myself that I had always behaved in a manner which reflected Honour on my Feelings and Refinement, I paid little attention to what she said…

As might be expected, Austen’s sense of the ridiculous allows her to avoid such silliness as the ‘African Olympic Games’ but, as with most juvenilia, it is of interest primarily in the light of what comes after. The presence of names such as Dashwood, Willoughby, and Musgrove in this collection rather emphasize than dispel that unfortunate association.

continuity

10 April 2004, around 9.54.

Citation (21)

11 April 2004, around 18.50.

…for certainly Life is so Pretious, as it ought not to be Ventured, where there is no Honour to be Gain’d in the Hazard, for Death seems Terrible, I am sure it doth to Me, there is nothing I Dread more than Death, I do not mean the Strokes of Death, nor the Pains, but the Oblivion in Death, I fear not Death’s Dart so much as Death’s Dungeon, for I could willingly part with my Present Life, to have it Redoubled in after Memory, and would willingly Die in my Self, so I might Live in my Friends; Such a Life have I with you, and you with me, our Persons being at a Distance, we live to each other no otherwise than if we were Dead, for Absence is a Present Death, as Memory is a Future Life; and so many Friends as Remember me, so many Lives I have, indeed so many Brains as Remember me, so many Lives I have, whether they be Friends or Foes, onely in my Friends Brains I am Better Entertained; And this is the Reason I Retire so much from the Sight of the World, for the Love of Life and Fear of Death…

exquisite

19 April 2004, around 22.33.

meme (ex machina):1

Intrigue me?2 The impression is that the lay-out of the whole area resembled that of the Seraglio in Constantinople, with palaces, barracks, and other royal buildings set in an area of parkland.3 A house of sin you may call it, but not a house of darkness, for the candles are never out; and it is like those countries far in the North, where it is as clear at mid-night as at mid-day.4 It can infuse vehemence and passion into spoken words in many ways, and when combined with argumentative passages it not only persuades the auditor but actually enslaves him.5 Wheresoever a thinker appeared, there in the thing he thought-of was a contribution, accession, a change or revolution made.6 The duke himself only rarely paid a visit north of the rivers and, when he did, stayed only briefly.7

- Take the nearest six to ten books from your shelf; open them to page 23, and find the fifth sentence: write down those sentences and arrange them to form a short story; post the text in your journal along with these instructions. [↩]

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida [↩]

- Peter Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria, vol. 1 [↩]

- John Earle, Microcosmography [↩]

- [Longinus], Libellus de Sublimitate (15.9). The actual passage runs as follows (I have not translated the bracketed material): [τί οὖν ἡ ῥητορικὴ φαντασία δύναται;] πολλὰ μὲν ἴσως καὶ ἄλλα τοῖς λόγοις ἐναγώνια καὶ ἐμπαθῆ προσεισφέρειν, κατακιρναμένη μέντοι ταῖς πραγματικαῖς ἐπιχειρήσεσιν οὐ πείθει τὸν ἀκροατὴν μόνον, ἀλλὰ καὶ δουλοῦται. [↩]

- Thomas Carlyle, On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History [↩]

- Jonathan I. Israel, The Dutch Republic [↩]

ablative abecedarian

20 April 2004, around 13.49.

· anodyne · bask · charming · destitution · emperish · fret · grapple · hebetude · incendiary · jest · kairos · lassitude · Mephistopheles · notoriety · omphalos · presume · quiff · restraint · sumptuous · tergiversate · unctuous · vertiginous · waffle · xiphoid · yare · zealous ·

experimentalist

21 April 2004, around 8.15.

…the judgement that someone is unliterary is like the judgement ‘This man is not in love’, whereas the judgement that my taste is bad is more like ‘This man is in love, but with a frightful woman’. And just as the mere fact that a man of sense and breeding loves a woman we dislike properly and inevitably makes us consider her again and look for, and sometimes find, something in her we had not noticed before, so, in my system, the very fact that people, or even any one person, can well and truly read, and love for a lifetime, a book we had thought bad, will raise the suspicion that it cannot really be as bad as we thought. Sometimes, to be sure, our friend’s mistress remains in our eyes so plain, stupid and disagreeable that we can attribute his love only to the irrational and mysterious behaviour of hormones; similarly, the book he likes may continue to seem so bad that we have to attribute his liking to some early association or other psychological accident. But we must, and should, remain uncertain. Always, there may be something in it that we can’t see.

perspicable

23 April 2004, around 14.12.

Happily Miss Carridge was a woman of few words. When body odour and volubility meet, then there is no remedy (43).

* * *

Her mind was so collected that she saw clearly the impropriety of letting it appear so (79).

clouds

24 April 2004, around 22.09.

|

|

pseudaphoristica (10)

25 April 2004, around 8.08.

Only a fool would use a cleaver to lance a boil.

BONUS Epicurian Gnōmē!

Τῆς αὐταρκείας καρπὸς μέγιστος ἐλευθερία.

Freedom is the finest product of self-sufficiency.1

Yes, yes, I know karpos means ‘fruit’ or ‘harvest’ – but I don’t really like the idea of autarkeia (another tangled concept, but there’s no helping it) reaping the whirlwind. If you don’t like the translation of megistos (lit. greatest, largest) as ‘finest’, well, there it is – those who live by the LSJ die in the middle of Liddell.

[↩]

Murphy

25 April 2004, around 18.58.

An insidious book. I started and thought it an unhappy cross between Keep the Aspidistra Flying and Dubliners, but as I progressed it worked through me its tentacles and I cannot escape – I will (I must) quote about Miss Dow and her cabbages, and the eleutherian sentiments of an Irish fire, that will not burn behind the bars of the grate. Some of the foreshadowing is a bit heavy-handed (e.g. Murphy and the gas), but it is funny, though bleakly so. Yet most of its jokes cannot be drawn from their context; every paragraph, every word depends on its proper place in the narrative to be understood. The most melancholy sentence in the whole book is:

The end of the line skimmed the water, jerked upwards in a wild whirl, vanished joyfully in the dusk (158).

discoursing

27 April 2004, around 23.57.

A Man may make a Remark –

In itself – a quiet thing

That may furnish the Fuse unto a Spark

In dormant nature – lain –

Let us divide – with skill –

Let us discourse – with care –

Powder exists in Charcoal –

Before it exists in Fire –

ex magna turba…

29 April 2004, around 15.30.

Nihil mihi nunc scito tam deesse quam hominem eum, quocum omnia, que me cura aliqua adficiunt una communicem, qui me amet, qui sapiat, quicum ego cum loquar nihil fingam, nihil dissimulem, nihil obtegam. abest enim frater ἀφελέστατος et amantissimus. †Metellus† non homo, sed ‘litus atque aër’ et ‘solitudo mera’. tu autem, qui saepissime curam et angorem animi mei sermone et consilio levasti tuo, qui mihi et in publica re socius et in privatis omnibus conscius et omnium meorum sermonum et consiliorum particeps esse soles, ubinam es? ita sum ab omnibus destitutus ut tantum requietis habeam quantum cum uxore et filiola et mellito Cicerone consumitur. nam illae ambitiosae nostrae fucosaeque amicitiae sunt in quodam splendore forensi, fructum domesticum non habent. itaque cum bene completa domus est tempore matutino, cum ad forum stipati gregibus amicorum descendimus, reperire ex magna turba neminem possumus, quocum aut iocari libere aut suspirare familiariter possimus.